Your Guide to Disease Control for Wheat and Barley

Table of contents

-

Overview

-

Disease impact on yield

-

Factors affecting disease damage

-

Initial infection and development

-

Resistant varieties

-

Identification of common plant diseases

-

Net blotch

-

Powdery mildew

-

-

Conclusion and further reading

Foliar diseases in wheat and barley

Common plant diseases, especially diseases affecting major agricultural crops, can result in serious economic losses for agricultural producers. By controlling fungal plant diseases, farmers can save 125 million tons of food each year - that’s enough to feed 600 million people.

Fungicides are chemicals that inhibit the growth or development of fungal pathogens. They are important tools that farmers use to protect and maintain plant health, quality and yield. Unfortunately, certain species can become resistant to fungicides. It is an evolutionary process that builds up through the survival and spread of resistant fungi after repeated use of the same fungicide treatment.

Custodia™ 320 SC is registered for disease control/treatment in wheat and barley. The diseases it controls include net blotch (Pyrenophora teres) and leaf blotch (Rhynchosporium secalis) in barley; and glume blotch (Septoria nodorum), speckled leaf blotch (S. tritici), eye spot (Pseudocercosporella herpotri-choides), brown rust (Puccinia triticina) and powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis) in wheat.

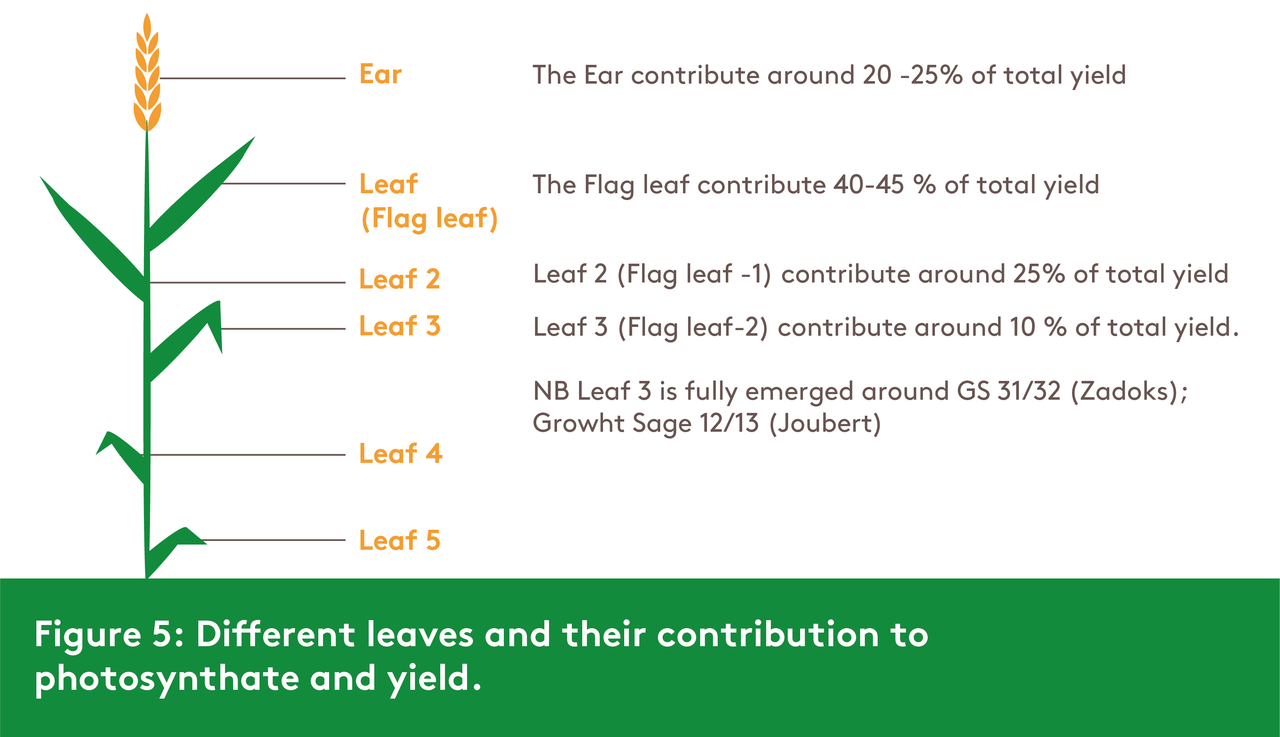

Most common leaf diseases (foliar diseases) accelerate senescence of the top three leaves, thus reducing yield and quality. Fungicide sprays during canopy growth prevent green leaf area loss during grain filling. These top three leaves contribute around 75% of photosynthate produced in wheat.

Timing of application is critical: by reducing the impact of the primary infection early in the growing season, the impact of the secondary infection may be less severe. Therefore some fungicide sprays should take place very early especially if the source of the pathogen is from stubble or seed.

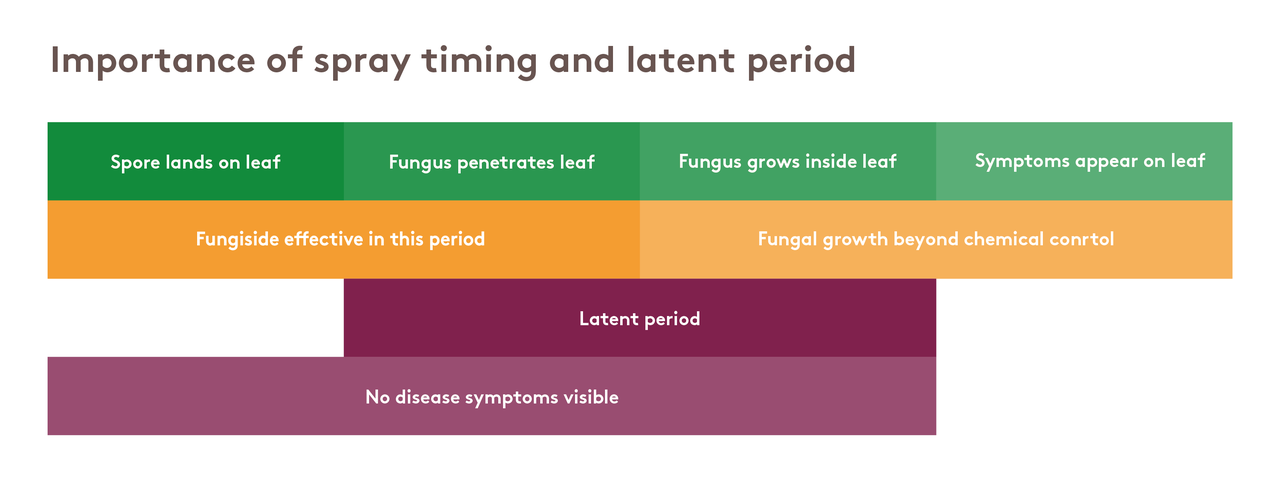

Infection is followed by a latent period when the fungus grows within the leaf, but no symptoms are visible. Eventually during the latent period the infection may be so far developed that fungicide applications may have little to no impact.

Preventative fungicide sprays are critical in the management of wheat and barley. Using an “all-rounder” fungicide like Custodia™ 320 SC in your spray programme can be your key to success.

Custodia contains azoxystrobin and tebuconazole. At one litre per hectare, Custodia™ 320 SC contains far more of these active ingredients than its competitors, making it a “heavy weight” in its class of fungicides.

Disease impact on yield

By reducing photosynthesis, inhibiting the translocation of photosynthate and by increasing plant respiration, foliar diseases inhibit the grain filling process. This results in a reduction in kernel weight and an increase in screenings.

Around 75% of wheat grain filling occurs within the first 4-6 weeks after head emergence. During this period, it is very important to minimise the severity of disease, especially in the top three leaves, as they contribute the most photosynthate to grain filling.

(Learn more about the most effective techniques for increasing wheat yields.)

Factors affecting disease damage

For a disease outbreak to occur, a virulent pathogen, a susceptible host for the pathogen and a favourable environment for the pathogen, must all be present.

Differences in the likelihood - & severity of damage, among the foliar diseases of wheat and barley, should be accounted for. Some diseases may be prevalent, but rarely cause significant damage, whereas other diseases are rare, but they can cause severe yield loss in certain seasons. When making management decisions, it is important to take all the risk factors into account and to identify the relevant disease accurately.

Initial infection and development

Infection usually results from spores moving into the crop. Depending on the specific disease, infection is followed by a “latent period” when the fungus grows within the leaf but the leaf exhibits no symptoms.

The cycle of leaf emergence, infection, latent period and symptom expression applies to all foliar diseases. The latent period varies considerably between pathogens and is affected by temperature. Many modern fungicides can control disease after a leaf becomes infected but only for about half of the latent period. Although there may be no symptoms on a leaf, infection may be so far into the latent period that no fungicide at any dose will control the fungus.

Septoria tritici has a very long latent period of about 14–28 days, but latent periods can be as short as 4–5 days for mildew and brown rust. Strategies to manage these diseases depend largely on protecting leaves as they emerge

Resistant varieties

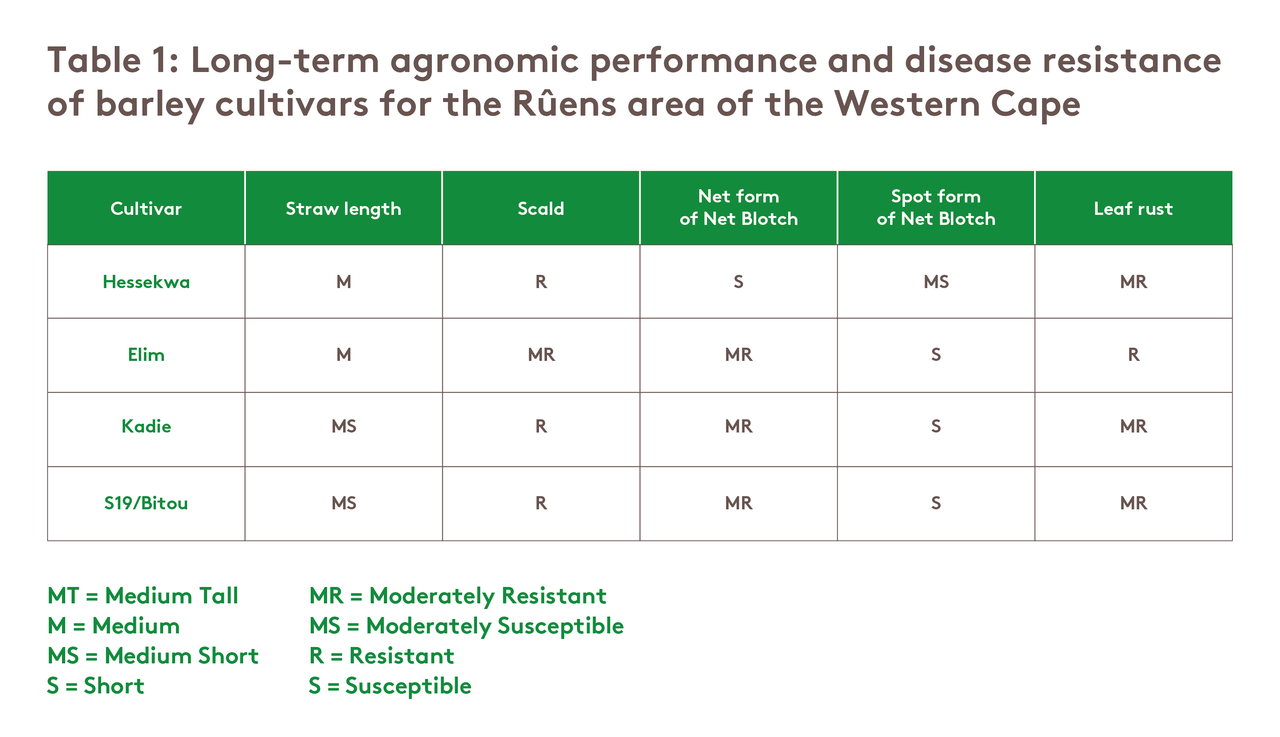

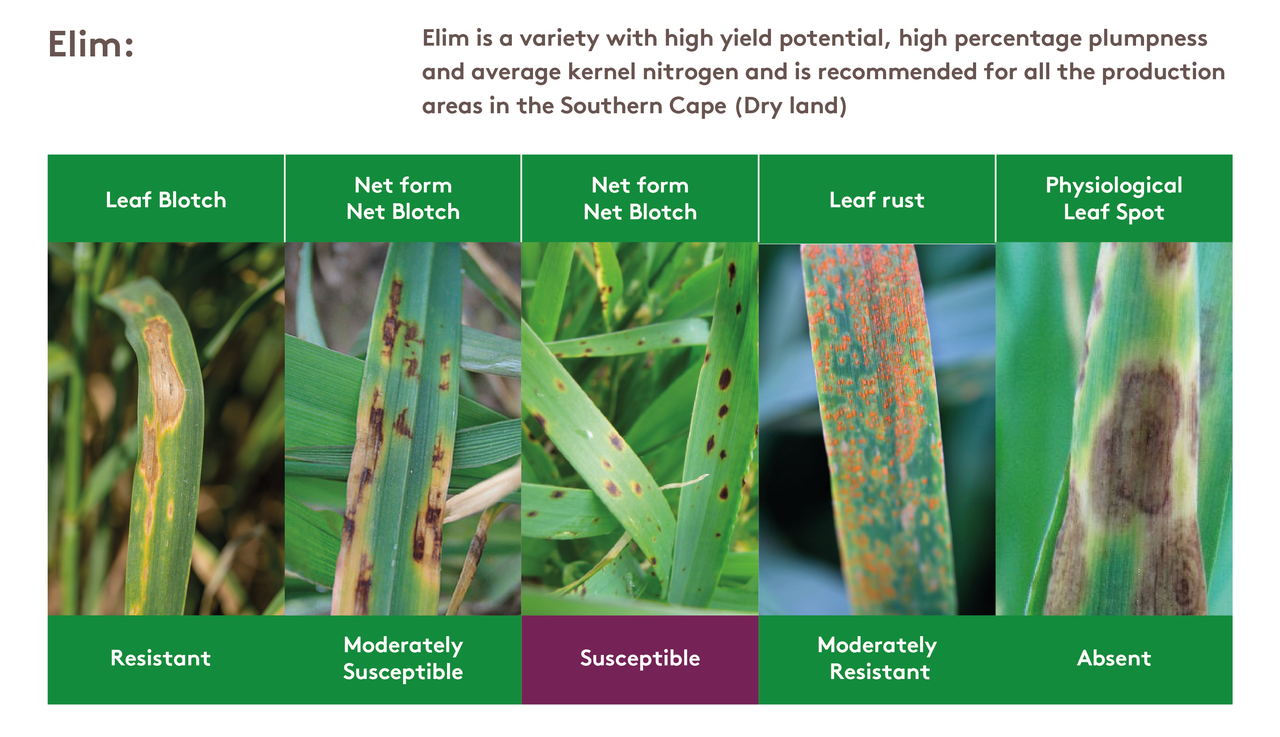

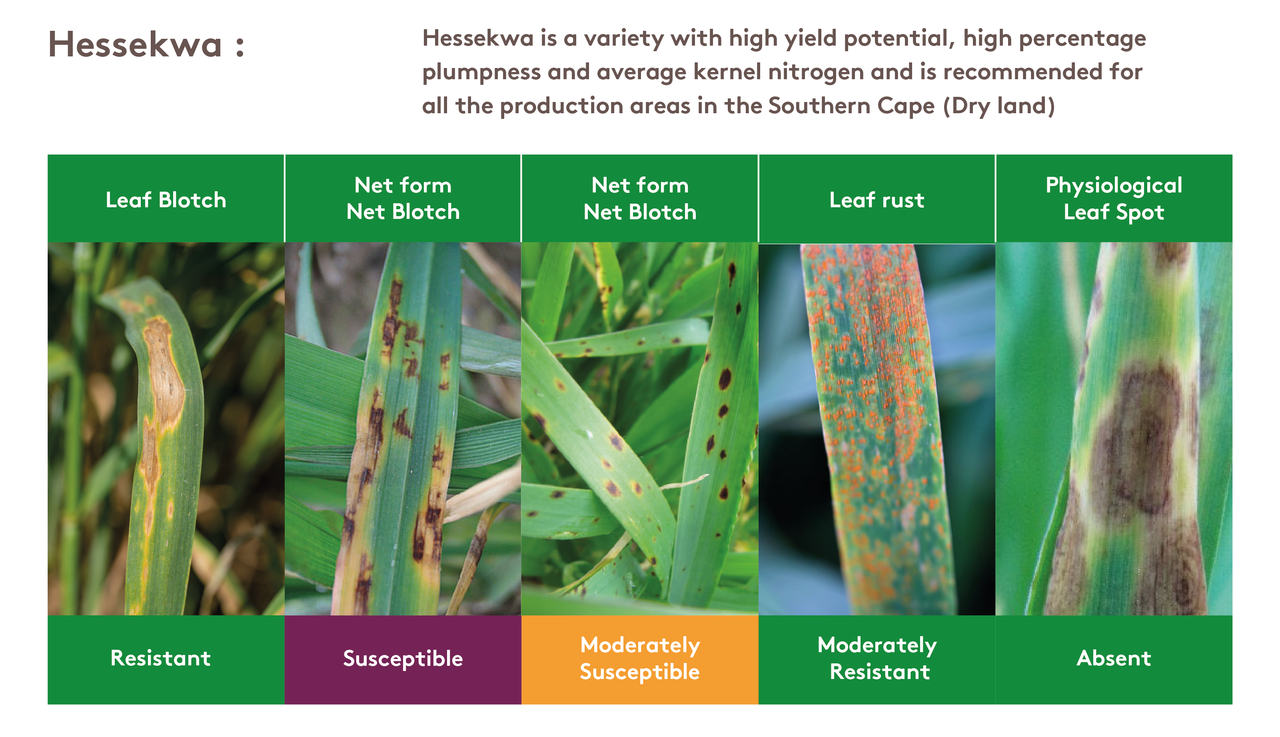

Some varieties may be more resistant to a specific pathogen than others. It is therefore important to always use the latest cereal disease ratings. Refer to your seed supplier’s agronomic data for disease-resistance ratings.

The more resistant a variety is, the less chance it will need additional protection from fungicides for that disease. Resistant varieties should be the first option in disease management, but adequate resistance to all important diseases is not often available in all varieties.

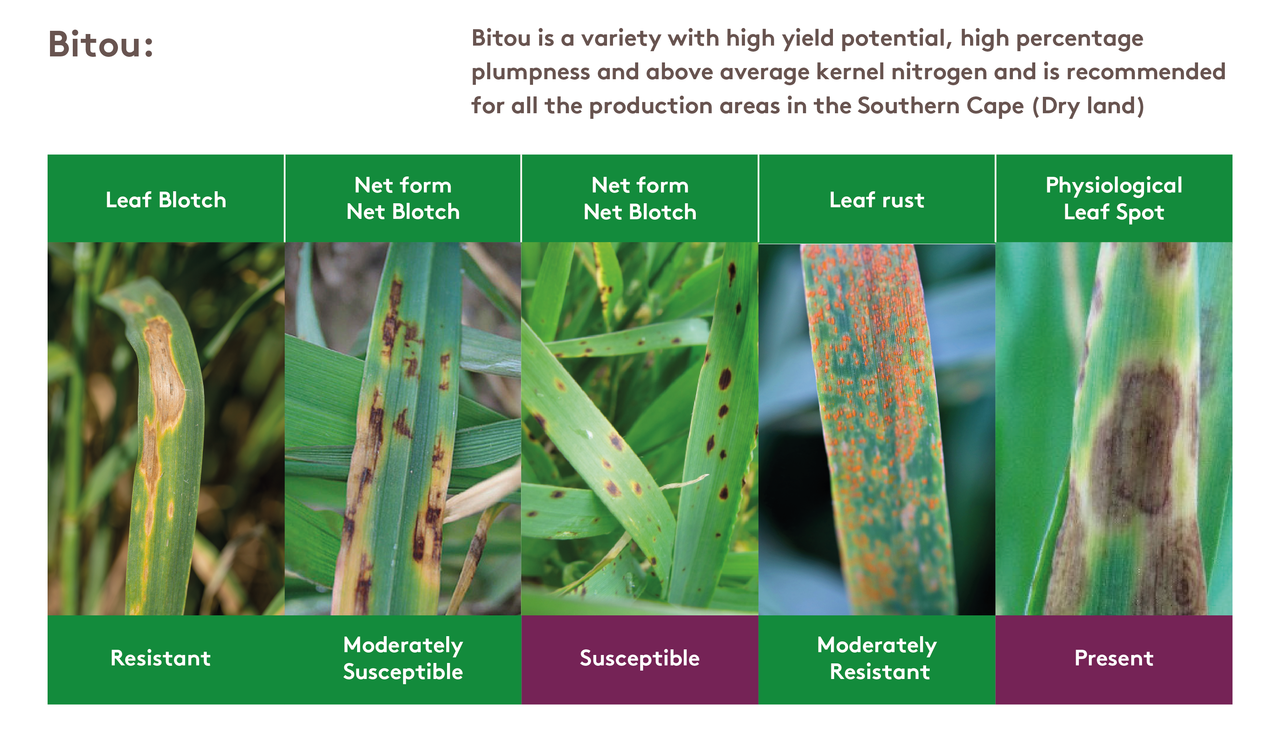

Note: S19 is also known as Bitou

Identification of common plant diseases in wheat and barley in the Western Cape

Cereal farmers in the production areas of the Western Cape of South Africa, are mainly confronted with these following foliar diseases:

Wheat:

- Mycosphaerella graminicola is a high host-specific pathogen, causing Septoria tritici leaf blotch of wheat.

- Phaeosphaeria (Parastagonospora) nodorum, is a major fungal pathogen of wheat, causing the disease Septoria nodorum blotch, also known as leaf and glume blotch.

- Puccinia striiformis causes yellow rust or stripe rust; Puccinia triticina causes brown rust or leaf rust; and stem rust of wheat is caused by the pathogen Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici.

- Powdery mildew in wheat is caused by the pathogen Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici.

Barley:

- Rhynchosporium secalis causes scald or leaf blotch

- Ramularia collo-cygni causes Ramularia leaf spot

- Net blotch is caused by Pyrenophora teres f.sp.teres and Pyrenophora teres f.sp.maculata (spot form)

(Read our advice regarding the control of powdery mildew on barley.)

Net blotch (Barley)

Pyrenophora teres

Symptoms

Depending on the source of infection, symptoms of Net blotch may vary. If infection starts from seed, brown stripes normally spread from the base of the leaves in seedlings and tillering plants.

If infection starts from crop debris or neighbouring plants, long brown lesions are visible with a netted or mottled appearance.

Affected leaves die back and the most serious symptoms usually occur on the upper leaves on unprotected or susceptible varieties.

Risk factors

Net blotch is a serious disease that may cause large yield losses when left uncontrolled.

Sources are infected seed, trash (barley debris from the previous year), volunteers and airborne spores.

Net blotch thrives in mild temperatures and wet weather. Second year barley crops, especially in a zero-till or no-till production system, are very favourable for high disease pressure.

Control

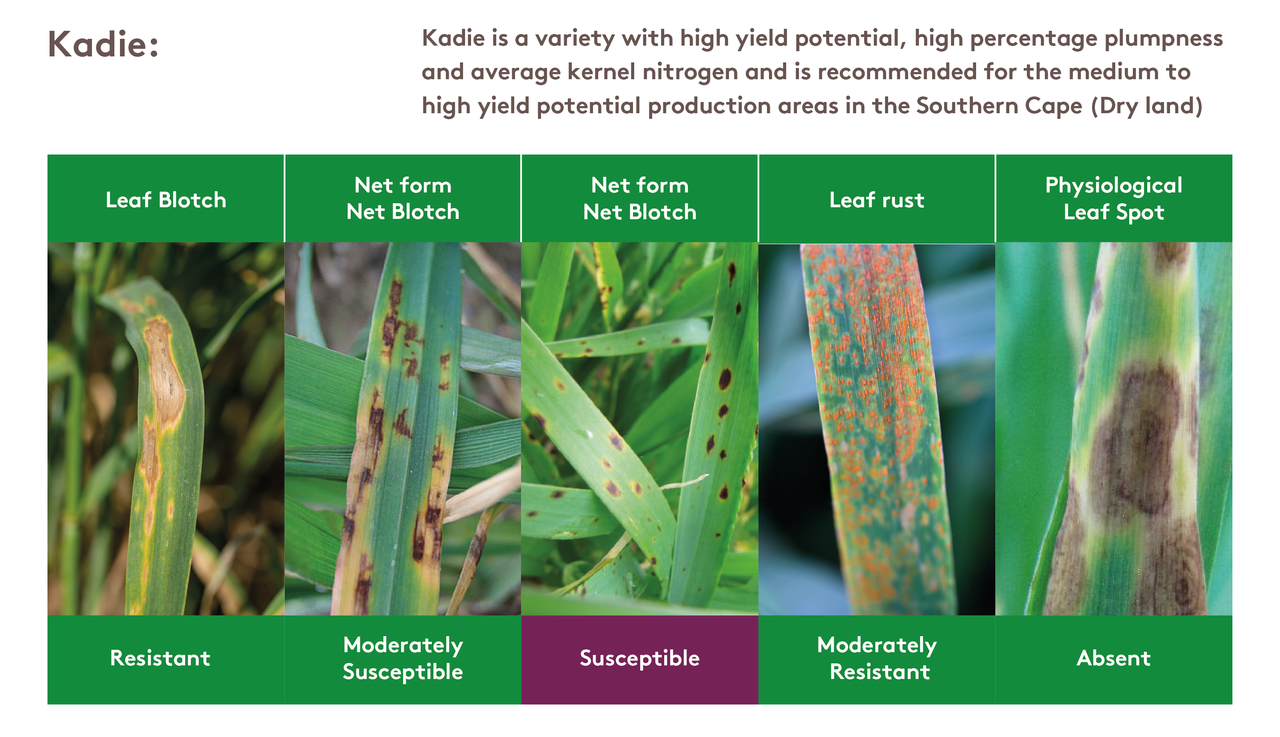

Sabbi’s production guidelines show that the cultivars Kadie and Elim, both have moderate resistance to Net form net blotch, while Hessekwa seems to be susceptible to the net form variant. S19 (aka Bitou) shows moderate susceptibility to the net form variant of net blotch.

Minimising the previous year’s crop debris; using appropriate seed treatment on infected seed; and managing the application of nitrogen based fertilisers, may all be cultural practices to consider in the fight against disease pressure.

By applying foliar fungicides against net blotch, farmers get a substantial return on their investment.

- Some triazoles are effective, but especially prothioconazole, seems to be most effective within the triazole group.

- In the Western Cape of South Africa, strobilurins show good efficacy, although widespread insensitivity is prevalent in the UK and other parts of the world.

- The SDHI fungicides (most of them are mixed with strobilurins and or triazoles) also perform very well against net blotch.

Timing of application is critical for the control of net blotch. Disease management in spring barley aims to provide early protection for developing tillers. Timing is influenced by sowing date and disease risk of site and - variety.

Remember the following key points:

– Foliar diseases can reduce tiller numbers.

– Barley is less able than wheat to recover from early disease effects on tillering.

– Disease management must start early to protect tillering and the developing ears.

– Season-long protection maximises grain storage capacity.

– For difficult to control diseases, early fungicide application may prevent epidemics.

Recommended control

To control net blotch, ADAMA recommends the use of Custodia™ 320 SC as a preventative fungicide. Custodia™ 320 SC contains azoxystrobin and tebuconazole. ADAMA has done extensive commercial trials, showing farmers that Custodia™ 320 SC performs brilliantly against net blotch and other foliar diseases. Within commercial trials with Custodia™ 320 SC in a spray programme, plots treated with this fungicide gave similar control of net blotch to competing SDHI fungicides.

Powdery mildew (Wheat)

Blumeria graminis

Symptoms

White fluffy colonies of pustules (containing conidia) often occur on leaves. Severe mildew can cover almost the entire leaf surface and develop on ears and stems. Later in the season, pinhead-sized, black fruiting bodies (cleistothecia) that produce sexual spores (ascospores) may be found on the white colonies.

Life cycle

Airborne conidia, produced on nearby wheat crops or volunteers, enable mildew to spread widely. Warm (15–22°C), breezy conditions with periods of high humidity favour infection.

New pustules are produced in 5–14 days. Temperatures over 25°C, and rain can inhibit development.

Sexually-produced spores provide a mechanism for summer survival via cleistothecia situated on crop debris, which contain the ascospores. These ascospores are responsible for early infection because the cleistothecia swell with rainfall, releasing ascospores that result in primary infection. Mycelium develops on young plants and conidia is released and distributed via air circulation, resulting in re-infection.

(HGCA Wheat disease management guide, www.researchgate.net/)

Risk factors

In South Africa, most cultivars are susceptible, with no cultivar showing any form of resistance. Primary infection takes place early in the season via ascospores, which are released from cleistothecia after rainfall.

Secondary infection via conidia increases the rate of infection, especially if the conditions are favourable with high humidity. This results in a “wildfire” of mildew infection. High-nitrogen-based fertiliser programmes worsen the disease pressure, resulting in excessive vegetative growth and poor air flow.

Warmer periods with a high humidity favour mildew outbreaks.

Control

Timing of application is critical as powdery mildew has a very short latent period. By reducing the impact of the primary infection (via ascospores) early in the growing season, the impact of the secondary infection (via conidia) may be less dramatic.

To ensure adequate protection of the key yield-forming leaves, fungicide treatments should be targeted to leaf emergence, rather than growth stage. Full emergence of leaf 3 usually coincides with GS32 but this can vary.

Leaf emergence is therefore the best guide for decisions on spray timing.

Some agronomists recommend four spay windows for wheat production, with the main application windows being T1 and T2. But when fighting powdery mildew, the strategy may be a little different.

Fungicides with specific activity against mildew are required where the disease is a particular threat. Treatments applied at T0 or T1, provide long-term protection.

(HGCA Wheat disease management guide, http://adlib.everysite.co.uk/resources/000/160/665/G54_Wheat_disease_management_guide_2012.pdf)

By looking at the graph above, the green area index shows total vegetative index.

Timing 1, -2, & -3, for spray applications are shown together with the Zadoks growth stage

Leaf 1 (Flag leaf) , Leaf 2 & Leaf 3 - Contributing to Yield

(HGCA Wheat disease management guide, http://adlib.everysite.co.uk/resources/000/160/665/G54_Wheat_disease_management_guide_2012.pdf)

For optimum protection against diseases, it is very important to protect the top 3 leaves and the ear as their contribution to photosynthesis are the greatest. Be advised, leaf 3 is fully emerged at GS 32, therefore when spraying fungicides at T1, almost 50% of the total vegetative growth has already been reached (refer to figure 4).

In the fight against powdery mildew, the first application should take place around 2-4 weeks earlier (T 0).

(ARC-SMALL GRAIN, Production of Small Grains in the winter rainfall area, 2020, https://www.arc.agric.za/arc-sgi/Documents/2020%20Production%20Guidelines/2020%20Guideline%20for%20the%20production%20of%20small%20grains%20in%20the%20winter%20rainfall%20area.pdf)

Recommended Control

In a spray programme aimed at the control of powdery mildew and other diseases such as Septoria tritici and stripe rust, ADAMA recommends the use of Custodia™ 320 SC as a preventative fungicide.

Conclusion and further reading

Preventative fungicide sprays are critical in the management of wheat and barley. Using an “all-rounder” fungicide like Custodia™ 320 SC in your spray programme can be your key to success.

Custodia contains azoxystrobin and tebuconazole. At one litre per hectare, Custodia™ 320 SC contains far more of these active ingredients than its competitors, making it a “heavy weight” in its class of fungicides.

For more information on CustodiaTM 320 SC, please download our overview. Remember to always check the label for good agricultural practices specific to this fungicide, and the dosage for each crop.

If you have any further questions about the control of diseases, pests or weeds, please email ADAMA infocpt@adama.com (Cape Town) or infojhb@adama.com (Johannesburg), or pop us a note here. One of our experts will be happy to advise you.

PS Barley has been tested extensively and found to have enormous potential for drought tolerance PLUS its root system can grow to lengths of two metres, binding the soil and preventing erosion. It is also an excellent option for crop rotation. Find out more about this crop and the contribution it can make to food security.